My initial experience with meditation was sitting in a dark room with no instructions whatsoever, and I spontaneously went into some kind of deep state of profound awareness. This led me to trust spontaneous realization in myself and others. People who think that all knowledge and all blessings come from India, or Tibet, or a Lineage, or the Guru have always seemed strange to me – the poor things, they don't know what they have inside. They tend to develop an unhealthy over-dependence upon externals.

It happened this way. I was in a class at the University of California at Irvine, in 1968, and a graduate student came around with a clipboard, signing people up to take part in a psychology experiment. I was a Social Science major and we were required to spend x number of hours each quarter participating in experiments. The study sounded exciting – it was about brain waves (EEG) and brain wave biofeedback. But of course, only the experimental subjects got brain-wave biofeedback. There was also a control group that got no feedback. Someone flipped a coin and my name was selected as a control subject; so I received no instructions whatever, no feedback. The grad student was very careful to not tell me what the study was about, and to be completely neutral in his attitude. I was just wired up and left there in a room that was utterly blacked out and soundproofed. I had never heard of meditation, and I had never sat in a dark room for several hours before, so I simply noticed what was going on. Gradually my senses opened up in ways that I had no words to describe.

After walking out of the lab each afternoon, I felt refreshed and wonderful. It was as if my entire previous life had taken place in a mild sleep state, and now I was really awake. Everything alive seemed to glow, especially the trees.

I felt in love with existence. It was as if I had never seen the world before.

I began to appreciate every detail of light, every touch of air, every sound, in a way I had never imagined. The feeling was somewhat similar to the joy I had after surfing or sailing my catamaran on the ocean all day, but more intense and steady. My mind was so clear that I found it easy to write essays in literature class, then turn them in before the hour was up, satisfied that I had done my best. Even taking calculus tests was easier – I could remember a formula that I had simply looked at the night before, and then derive its applications right there during the test. This heightened clarity of sensing lasted for weeks after the experiment was over.

When I went into that dark room in early 1968, sitting there with EEG wires on my head, three hours a day, five days a week for several weeks as part of the lab experiment, I had not even heard the word, "meditation."

When the experiment ended, I missed having those hours in the dark room, so I set up a little room off the garage at home and would sit there, exploring different techniques. At first I just sat there doing nothing. But just being there in a garage, with the afternoon light coming through a little garage-type window was not as conducive as being in a soundproofed, totally dark lab.

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

The first book on meditation I ever saw was by Paul Reps, and it really clicked. Twenty years later, in 1988 I started working on my own version of the ancient text, here are some notes to my version of this text, which I call The Radiance Sutras.

By coincidence or grace, the first thing that I ever read on meditation was the English translation of the Bhairava Tantra by Paul Reps, contained in Zen Flesh, Zen Bones (Doubleday, 1957). It was 1968. I was 18, a freshman at the University of California. In the physiology lab where I worked, a woman graduate student - Betty - happened to show me the book one day for a few minutes, because she was delighted with it. The verses reminded me of something I had experienced two months before, when I had participated in an experiment in which I sat in a totally dark room for three hours every day for three weeks.

Then the woman, whom I knew only slightly, handed me the little book. It seemed to speak right to the heart of those experiences that I underwent while sitting in the dark room and afterwards.

This is the page I opened to:

My attention went to ". . . this experience may dawn between two breaths. After breath comes in and just before turning up – the beneficence. As breath turns from down to up – through both these turns, realize."

Something happened in me when I read that, a quiet cool flashbulb. It was the first thing I had seen that said, "Someone else has experienced what you experienced." It is known, and repeatable, and you can go there again.

I had been feeling exiled from that place. Couldn't find my way back in. Now I sensed I could see the trail.

I read the first few lines of this page and took a breath. I was instantly in love with this teaching, excited by it. I asked her if I could borrow the book, and she said no, so I asked where she bought it, which was a bookstore in a nearby shopping mall. So I went straight there and bought a copy. By some miracle, I still have the copy I bought that day. It is falling apart, as paperback books tend to.

Here is a scan of that copy.

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

This book is still in print, but with a different cover. Here is an Amazon link.

The experience in the lab taught me that meditative attention occurs to people spontaneously, if given a suitable situation - in my case, I had nothing else to do in that blacked-out room for two or three hours. From the Bhairava Tantra I learned that there are many gateways into meditation, many types of touch, breath, sights, sounds that can be used as vehicles for the movement of attention. Meditation experience is immediate and sensuous, although there are far ranges of it that are so refined that people mistakenly believe are “beyond the senses.”

Paul Reps and Laksman Joo

How did Zen Flesh, Zen Bones come to have a chapter on the Bhairava Tantra? Paul Reps learned about the text from Laksman Joo, whom he met in Kashmir. In Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, Reps writes:

“Wandering in the ineffable beauty of Kashmir, above Srinagar I come across the hermitage of Laksmanjoo.

It overlooks green rice fields, the gardens of Shalimar and Nishat Bagh, lakes fringed with lotus. Water streams down from a mountaintop.

Here Laksmanjoo – tall, full bodied, shining – welcomes me. He shares with me this ancient teaching from the Vigyan Bhairava and Sochanda Tantra, both from about four thousand years ago, and from the Malini Vijaya Tantra, probably another thousand years older yet. It is an ancient teaching, copied and recopied countless times, and from it Laksmanjoo has made the beginnings of an English version. I transcribe it eleven more times to get it into the form given here.”

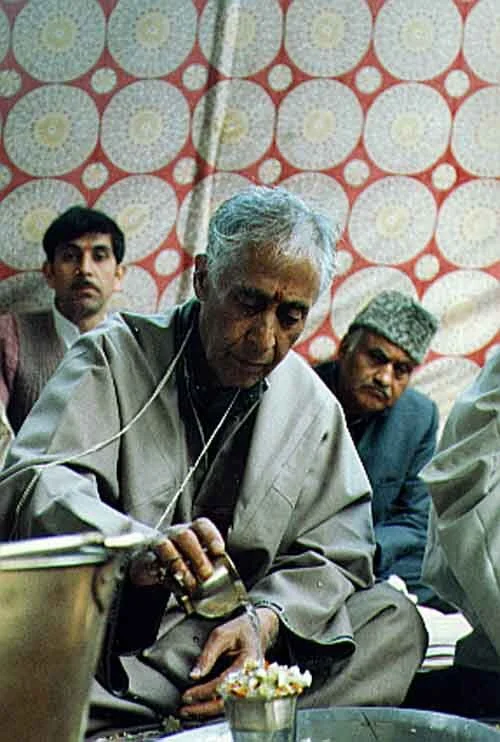

Laksman Joo doing a ritual

I never met Laksman Joo, I have only received his essence through meditating with the words he and Paul Reps developed for putting the Bhairava Tantra into English.

So then I started reading books and exploring various techniques. I read about autogenics, and did visualizations of my muscles relaxing. I read Psycho-Cybernetics, by Maxwell Maltz, and practiced the visualizations he talked about. I read The Secret of the Golden Flower, (I don't recommend this book) with a commentary by Jung, and experimented with the techniques described in there. I bought Tony Scott's MUSIC FOR ZEN MEDITATION AND OTHER JOYS and listened to it on a little record player and burned incense. I bought a book on yoga and practiced simple breathing techniques, inhale for some count, exhale for some other count. Breathe in through this nostril, breathe out through the other.

I went to the University library and spend entire evenings there, going up and down the psychology, sociology, and anthropology isles, looking for anything that spoke to the experiences I had in the lab. One evening I found Ecstasy: A Study of Some Secular and Religious Experiences, by Marghanita Laski, which seemed promising, but wasn't practical and experiential enough for me. Almost everything I found was too academic, too dry, analytical, and it seemed as if the authors had little or no direct experience with the richness of life.

One day I was reading PLAYBOY. I guess I religiously studied every page, looking for clues on how to live and love. There was a Letter to the Editor, in which some guy said, "I live in New York, and out on the street I saw some people dressed in orange, dancing and chanting HARRY BLAMA or something like that. What was that?"

The PLAYBOY Advisor replied, "Those are Hare Krishna devotees, and they were chanting:

HARE KRISHA

HARE KRISNA

KRISHA KRISHNA

HARE HARE

HARE RAMA

HARE RAMA

RAMA RAMA

HARE HARE

And loosely translated, this means:

LORD GOD

LORD GOD

GOD GOD

LORD LORD"

I wrote this all down on a 3x5 card, which I carried around with me and memorized over the next few days. Then each afternoon, when i would sit in the room off the garage, I would chant it quietly, both in Sanskrit and in English, then think it softly. I remember that wrinkled, crumpled card with blue ballpoint ink on it in the right hand pocket of my jeans. I liked both the English and the Sanskrit. This was probably the first time in my life I ever prayed.

Thinking Hare Krishna was beautiful. I did not know anything about how to pace myself, or how to handle things. I was thinking at the time that I should sit there for 45 minutes to an hour. I did not know then that this was way too long, especially for a beginner. Also, the incense did nothing for me except make me sneeze. Fresh air is so much better than incense.

I explored all sorts of combinations and permutations: pranayama + Tony Scott's album + incense + the Hare Krishna mantra, or Progressive Relaxation + pranayama. Or just sitting there.

This went on for a couple of months, with mixed success, and I was missing the intensity of relaxation that I had while in the lab.

So it was that I began systematic study of yoga asanas, pranayama, meditation and mantra, and I began to encounter teachers of many kinds. The teachers gave me invaluable tools and the blessing of their skilled attention, but I always knew the wellspring of the teaching is within. I have the sense now that there was a good plan behind this wacky, off-the-cuff, improvisational way I fell into meditation, or fell in love with meditation.